Welcome, bubbleheads. A look at a slightly contentious topic this week : the market for Champagne, with thanks to merchant and investment specialist Sara Danese.

Also, a quick note to say that the England Special Report 2022 is finally here! A real labour of love this year, with almost 300 wines tasted, fourteen awards, in-depth analysis and a feature on England's most forward-looking viticulture. Download it here.

2013s taking their time in the Salon cellars, Le Mesnil-sur-Oger

If, like me, the Metas and Googles of this world have worked out that you like decent wine, then you’ll probably have been bombarded by online advertising about various ‘inflation-busting’ wine investment packages recently. The last one I saw splattered a few graphs about Domaine de la Romanée Conti about, whose wines have unsurprisingly risen rather a lot in value. Taking these as evidence for wine’s investment potential as a whole, though, is a little far-fetched.

Wine can, of course, make money. Champagne has not been the first port of call in the past, though, thanks to its reputation for immediacy rather than longevity. Some of this perception persists: consider this article from Bordeaux Index, which claims that Dom Perignon will be “…closest to the winemaker’s intention and the most intense expression of itself” in its first five years post-release.

A few Dom Perignon drinkers might raise a quizzical eyebrow at that statement. The market for Prestige Champagne is as hot as it ever has been, after all, and this is surely due to the fact that the lifespan of these wines is finally starting to be appreciated. In addition, Grower Champagne has joined the Premier League when it comes to the hype game, with canny buyers eyeing up the secondary market, spurred on by the astronomical increases in price achieved by the likes of Ulysse Collin and Cedric Bouchard. What could be driving these increases, which appear to be swimming against a widespread plateauing of fine wine prices?

The Champagne market, autumn 2022

Sara Danese is an entrepreneur in the fine wine trade. Educated in economics and finance from Imperial College and University of Padua, she previously worked as a portfolio analyst for a large asset manager. Four years ago, she founded AZYA, a digital fine wine trading company selling wines to China.

Combining her passion for both wine and investment, she curates a weekly publication for the next generation of wine lovers/investors called “In the mood for wine”.

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that investors must be in want of a bargain.

They are often suspicious, though, of markets that grow exponentially. As many of the same experienced investors will tell you, ‘fighting the trend’ is a very consuming (and costly) tilt at windmills. Momentum is to blame, a behavioural bias which plays on the herd instinct of people as they gravitate toward the same or similar investments as others. When more people invest, the market goes up, encouraging even more people to buy.

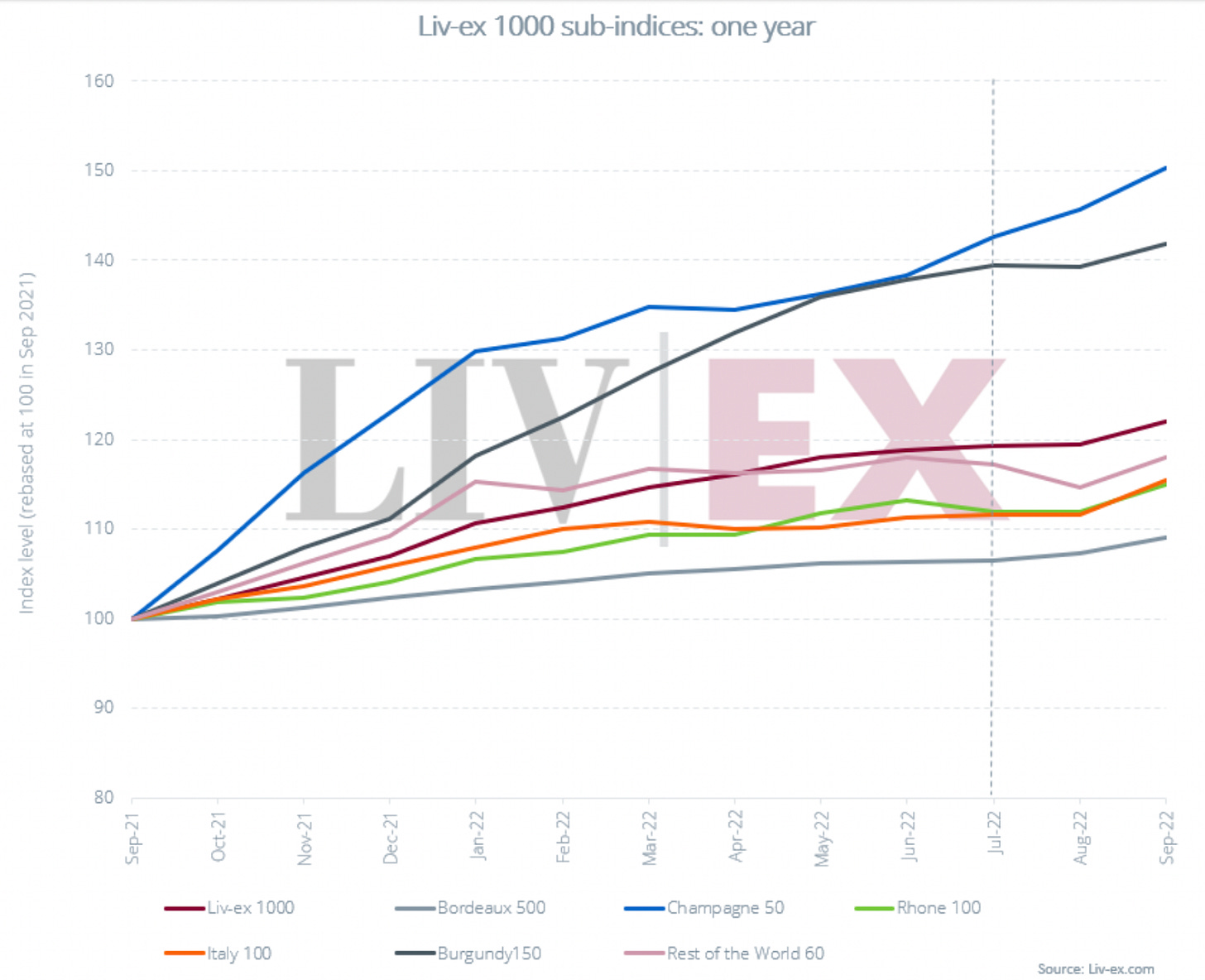

That the Champagne market is seeing such a virtuous cycle is undeniable. In the last year, as can be observed in the chart from Liv-ex (the leading fine wine index used by professional traders), the top 50 champagnes outperformed even Burgundy for the second year in a row. Essi Avellan MW, in her recently released Club Oenologique’s Champagne Report 2022, believes that the Champagne market is becoming so overheated that “some wines were rushed to release earlier than usual due to the huge demand” causing issues in some of the non-vintage wines which “failed to reach their standard level and was clearly due to shorter lees ageing or abbreviated post-disgorgement”.

Collectors might feel quite nervous, then, about investing in a bottle of Champagne at the moment. Is the bubble about to burst? A looming recession, a panicked stock market, a cold winter ahead of us and a war at the doorstep of Europe – can we expect the Champagne market to continue its run, or to hold its value?

An economic downturn will likely favour wines with a stable track record, a strong brand recognition and, perhaps more importantly, liquidity to sustain a period of relative instability – all requirements that are met by large Champagne brands. Looking at the components of the Champagne 50 index, for example.

Trades on Liv-ex indicate that wine merchants are trading some of these Champagnes at prices that are close to the retail in-bond prices.

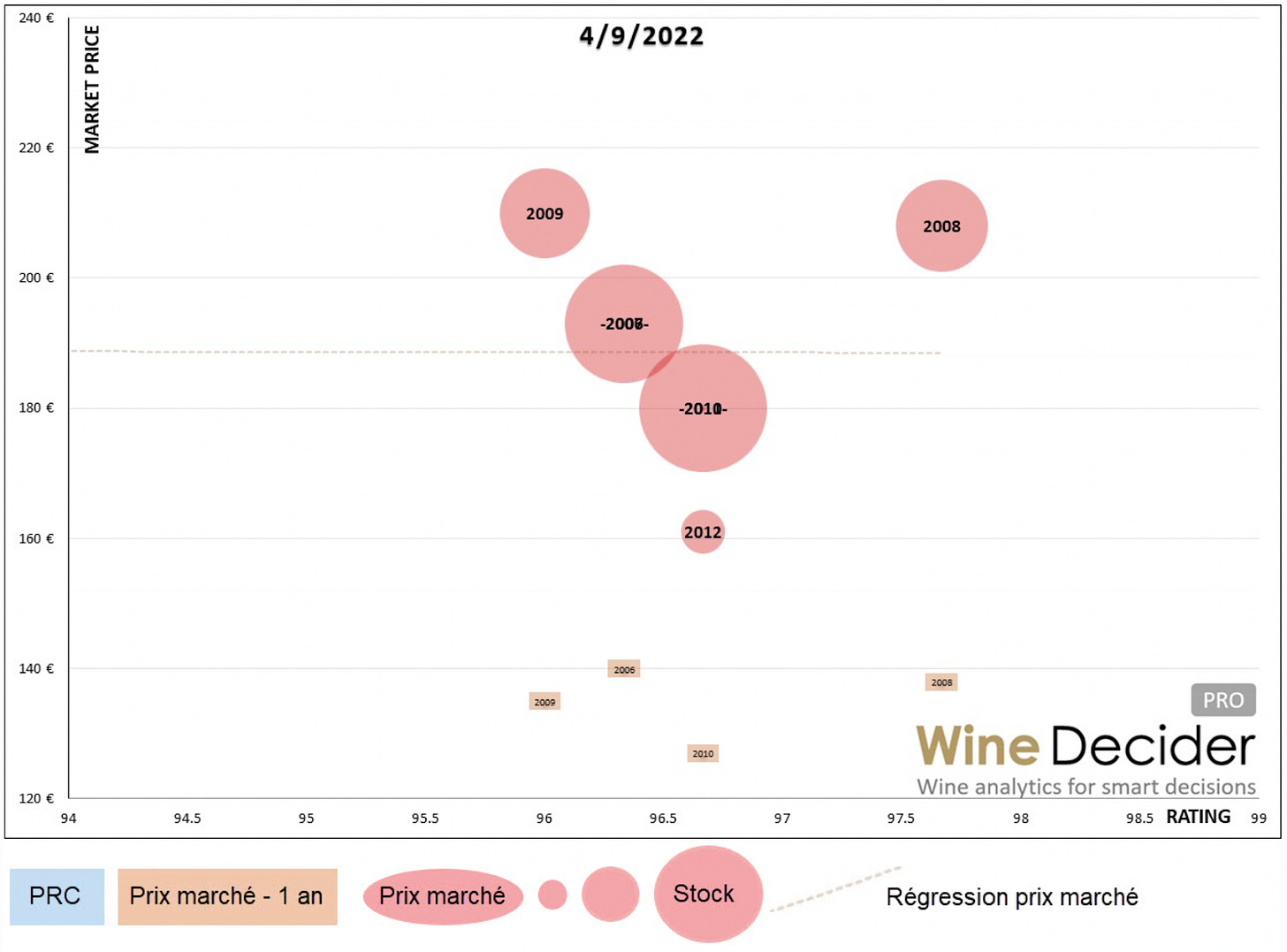

One explanation for this unusual phenomenon is that wine merchants are confident they will be able to shift such wines at increasingly higher prices in the future. Dom Pérignon 2012, for example, has underperformed the index so far year-to-date (+11.5% vs +22.3% YTD Champagne 50). However, the last traded price on Liv-ex is recorded at £166.7/bottle - the same price a retail customer could buy these wines. This dynamic is observed with other Champagnes, such as Piper-Heidsieck Rare Rosé 2008, Louis Roederer Cristal 2008, Taittinger Comtes de Champagne 2008 and Salon Cuvee 'S' Le Mesnil 2012.

An increase in price to at least that of the 2008 is to be expected, then, when accounting for the much more limited supply of Dom Pérignon 2012 (as reported by Wine Decider Pro, where the size of the circle corresponds to the vintage size).

Piper-Heidsieck Rare 2008 received a glowing review from Essi Avellan MW for Club Oenologique, and 98 points alongside Louis Roederer Cristal Rosé 2013, Dom Pérignon Plénitude 2 2003 and Laurent-Perrier Grand Siècle Les Réserves No 20 Magnum. To think that those champagnes go for £300 to £450 / bottle, Rare 2008 seems quite fairly priced at £116 / bottle. (Tom points out here that scores for Rare have been fairly Euro-centric, and that an upturn in reputation in the USA would probably send these prices considerably higher).

It’s always hard to find pockets of value in a rising market – more so than in a down market. However, market dynamics as well as supply and demand point at staying laser-focused on a few names that can weather the storm of a recession, offering better downside protection with the potential of increasing in value in next five years.

Thanks Sara - Back To Tom For A Few Final Thoughts.

Champagne’s Unique Position

Despite the heat in the market, there is a very specific dynamic to consider in Champagne: the rollout of vintages and stock levels. It looks like the only vintage since 2013 likely to go down as a classic will be 2019. Yes, there will be brilliant wines from almost every vintage in-between, but part of what makes a wine leave orbit is universally-agreed vintage quality, and that just doesn’t look like being settled on in 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 or 2018. Furthermore, a number of these were badly frost-affected, so quantities of whatever Prestige releases there are may be relatively small.

What’s more, with the exception of some 2014s, none of these vintages promise a cool, long-lived character; at best they are likely to come out rather sunny and generous. 2019 fights back, as will a small number of 2021s, but 2022 looks again to be a year for fairly voluminous wines. Style-wise, then. 2013, with its tension, acidity and longevity, looks like it might be a vintage to go long on with the wines still on the market (and still to release, such as Dom Perignon). Perhaps investors know that we may all be feeling a little starved of top vintages in a few years’ time.

Playing the Grower Game

“Which growers should I be buying?” remains one of the questions I’m asked most frequently. Speculation on wines made without much track record of ageing, though, is risky if undertaken for anything other than very short-term gain. It strikes me that those stocking up on very immediate, naturally-styled champagnes that go through the Hype Machine may find themselves sitting on cases that are over the hill if they think the wines will continue to improve for decades like the Prestige Cuvées they share their price point with. Some will, but many of them won’t.

What to look for, then?

Track record, top sites and a critical consensus on age-worthiness. Usually plenty of Chardonnay helps. Beware ultra-low SO2 regimes; not every producer pitches their wines for long ageing. Benoît Marguet, for example, wants maximum expressivity at release and, despite the price and reputation of the wines, makes few guarantees about long-term ageing on cork. It can be the same with producers such as Lassaigne and Leclapart; all deservedly sought-after wines, but ones that need careful consideration about when to drink. Investors will eventually pick up on wines that are too old, and it’s worth bearing in mind that some critics tend to over-estimate drinking windows in Champagne when the wines are already showing signs of rapid opening in youth.

Expense, then, is often a function of rarity more than longevity. Dropping serious money on Champagne still doesn’t look like a terrible idea - but knowing which you’re in for may be key to success.

Many thanks to Sara for her insights this week. If you’d like some picks, both for Growers and Houses, I’m afraid you’ll have to wait until the Tim Atkin Champagne Report 2022 comes out nearer Christmas.