Pragmysticism in Champagne

Sometimes the spiritual and the practical are two sides of the same coin

Welcome, bubbleheads.

Artisan Bakery or Vineyard Store? At Champagne Marguet in Ambonnay

Grapes have a habit of dishing out quantities of juice that don’t fit neatly into barrels and tanks (hence the ‘floating lid’ tanks you see in wineries). Well, the same is true of interviews and visits. Following on from How Moët Blend/Burning Corks, the next jugful of spillover from last year’s Champagne travels is all about my encounters with all things ephemeral, spiritual, reflective - or, if I were a killjoy, the plain superstitious - in the cellars of Champagne.

I’m a smile-and-nodder when it comes to that point in a visit where rocks hold memories, or barrels talk to each other, or plastic kills the soul of a wine. I know a few people that can’t resist an attempt to nudge an unwilling dreamer down a logic-lined path, while others take the mystic meanderings of some winemakers as evidence of greatness. Either way, a mind that is open just a squeeze - ajar, just wide enough for something small and persistent to force itself in (or let itself out) - is going to have more fun than one that is made up before it gets through the cellar doors.

Before you read on: I set myself a target of subscribers by my one year anniversary. It’s going well - I’m 70% there, with 4 months to go. If you haven’t already, do sign up for free, and share the newsletter with anyone that might like it. It really does keep the wind in the sails:

Exhibit A: Let’s Stay Together at Champagne Marguet in Ambonnay.

One of the first thing most people learn about Champagne is the way the grapes are pressed. The finest cuvée juice, the 2050 litres per 4000kg press load that gets released first, is the main event. The more intense, grippy and less-elegant tailles from the next 500 litres have to be separated out before being either blended back (usually into entry-level cuvées) or sold on. Beyond these 2550 litres, anything extracted is not allowed to become champagne.

Benoît Marguet is no stranger to a little friction with the rulebook, though. At Marguet’s home in the Grand Cru village of Ambonnay on the southern side of the Montagne de Reims, something happens that I’ve never encountered anywhere else - the cuvée and the taille don’t get separated. Marguet explains why:

“One day [the CIVC] came here. They tried to stop me. So I came out with some tasting notes where my work comes first, ahead of some prestige cuvées and famous champagnes, and I said “you cannot stop me”. A grape contains different kinds of juice, different kinds of seeds and sugars. If you’re a scientist you only think about that. But the unity, the energy of the one is important…if you split it and reassemble it then the damage is done”.

Marguet talks about his grapes, his juice and his wines as if they are people - not just alive, but sentient, sensitive. His methods create some workflows that most modern winery managers would find cumbersome, if not completely insane: there are no electronic devices in the winery (it’s phones off when you walk through the door), and hardly any pumps (despite the fact that everything is in barrel). All 300 barrels are physically lifted and poured into sizeable blending tanks by forklift when the champagnes are assembled. Perhaps it’s just as well Benoît doesn’t have to worry about cuvées and tailles as well.

Interventionism gets a bad name

Philosophies that might seem new-age-floaty on the surface tend to need practical regimes that are fanatically well-organised. There’s the religion, and there are the rites: a tour through Marguet’s sheds demonstrates just how involved these can be for an organic and biodynamic grower. There are row upon row of paper sacks and small tubs, more reminiscent of an artisanal bakery than an agricultural business, inside which everything from grapefruit oil (from one particular kind of grapefruit) to eucalyptus, grown by Benoît himself, talc, salts and herbs lie ready for very specific jobs. When asked what they do, there’s no mysticism - drying out, anti-fungal, heat stress. If it doesn’t prove itself to work, it’s out of the shed.

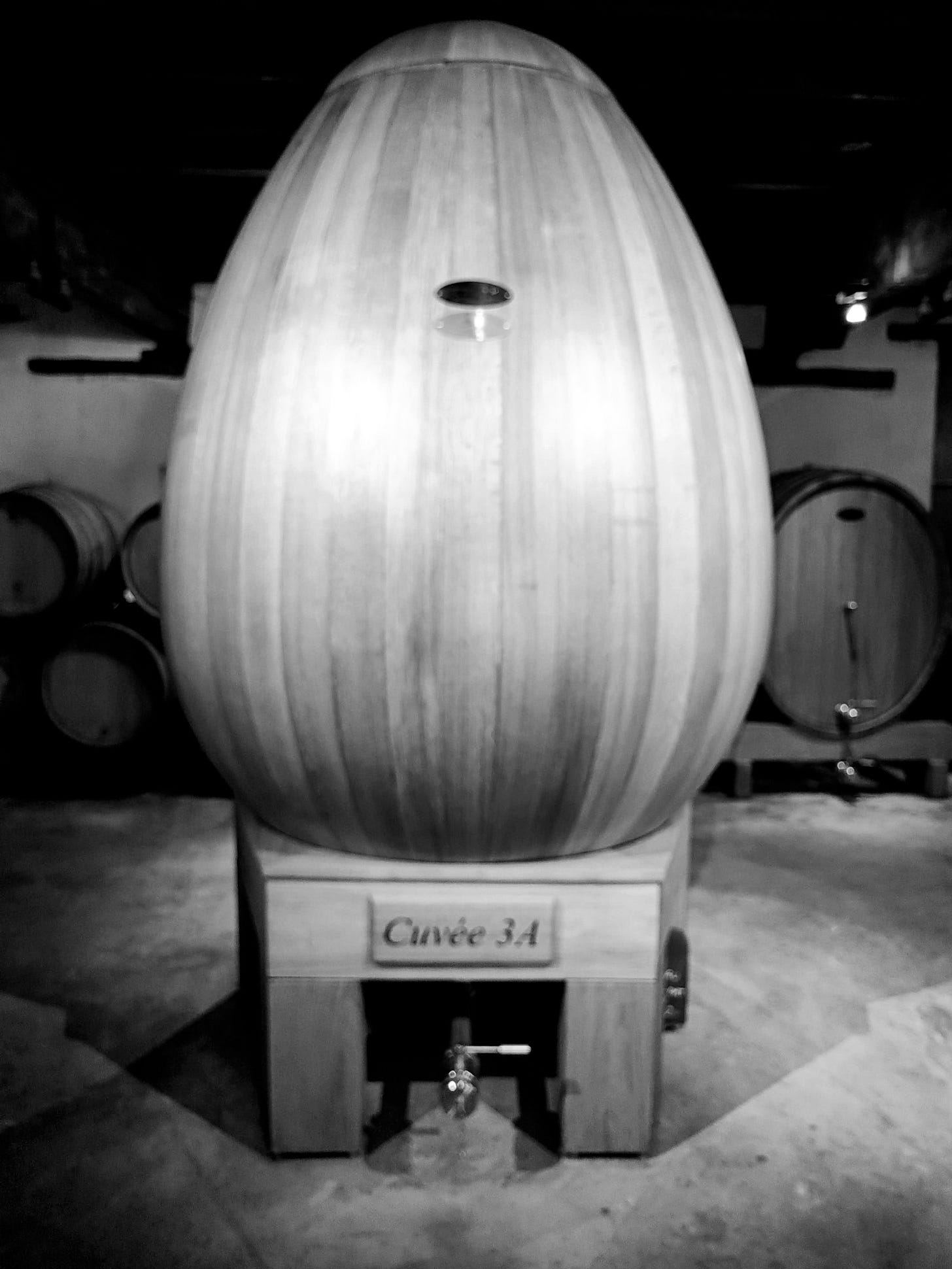

The lunar module - or wooden egg fermenter- at De Sousa in Avize

At Champagne De Sousa in Avize, another long-established biodynamic estate, Charlotte De Sousa points out that their vineyard areas is divided into parcels that average just 10 ares (or four tennis courts) each, mostly dotted around the Côte des Blancs but also on the Montagne de Reims and around Mardeuil in the Marne Valley. In 2021, their 93 plots needed constant protection: “It comes down to personal organisation, having a big team, having all the right materials and being reactive. When it rains every day, you have to cover the whole vineyard every day!” The sheer cost, in time and logistics, of managing estates like this without systemic products is not for everyone. One proprietor in Vertus told me she’d like to, but her estate was so fragmented - and surrounded so closely with conventional farmers - that it would be “impossible”.

Yes, at De Sousa (as elsewhere) there are crystals in the barrel room, sine waves being played to the wines, a distrust of satellite communications and electricity pylons, a general air of reverent spiritualism. But do the family spend their days sitting cross-legged watching their wines make themselves? Hardly.

Neither, though, do they seem to give the spiritual angle a hard sell to visitors. Sometimes it is the people whose wines seem to flow with the most confident naturalism that play host to the most pragmatic, direct conversations about making champagne. Elsewhere, behind the grander doors of Reims and Épernay, wines that are - and this is not a dig - technical accomplishments on a notable scale, sometimes have their stories told in flights of fancy.

In the end, making wine seems to involve praying to both gods. Luckily, they don’t see, to be jealous types.