(…and a quick reminder for those subscribers that can get to London that we have a brilliant bring-your-own event lined up on the 28th March - do come along!).

The Bubblehead BYO is on!

Let’s meet up and pop some corks! UK bubbleheads: I’m thrilled to have teamed up with my incredible friends Sarah and Dan at the frankly astonishingly-good Oeno Maris in Newington Green for a Bring-Your-Own-Bubbles evening on Thursday the 28th March, alongside a six-course showcase of some of London’s very, very best seafood. Dan is an actual Master Fish…

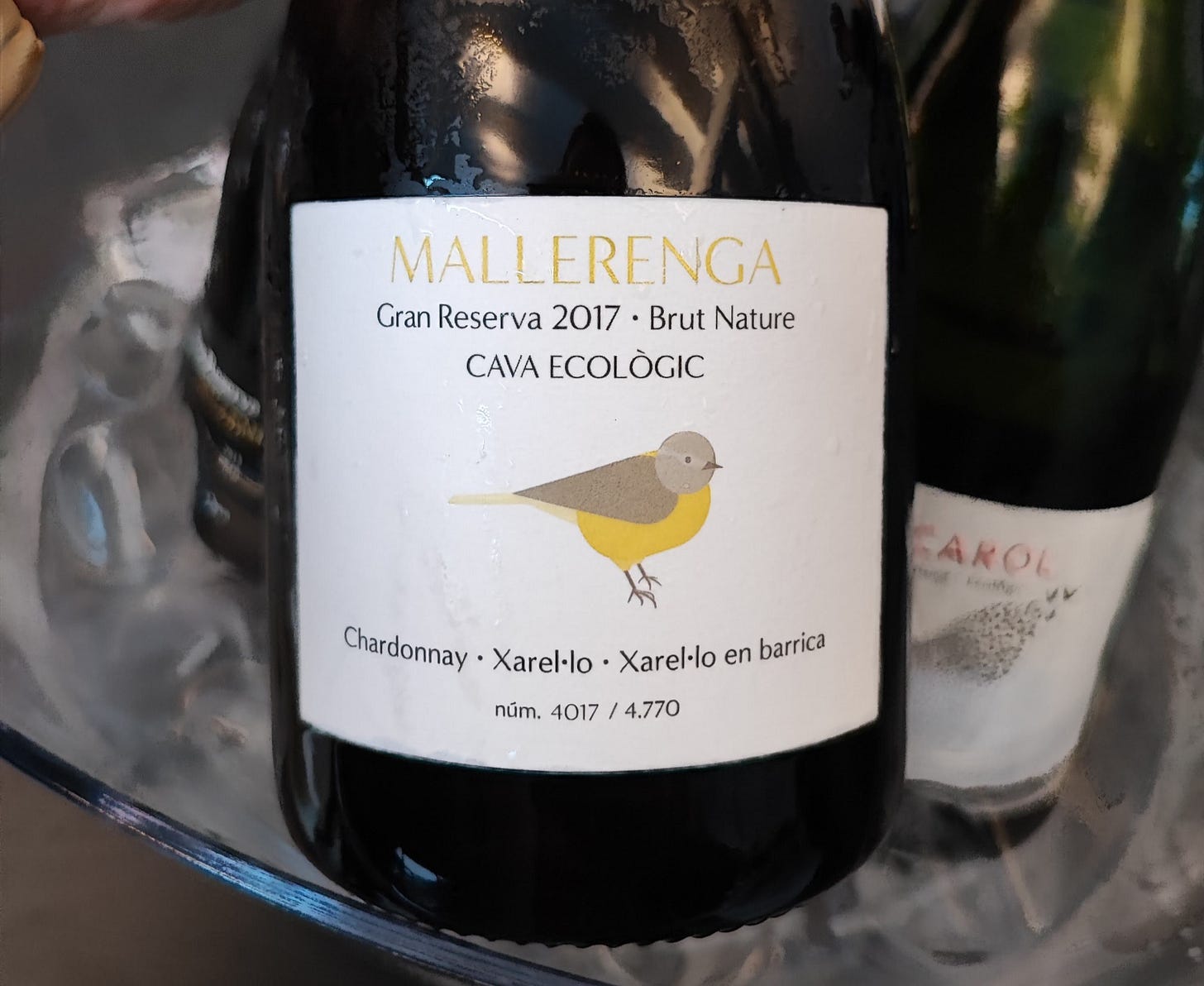

The following is an extract from the just-published timatkin.com Special Report on Catalan Sparkling Wines, which is available to download here:

Does top Cava need to prove itself with Olympian feats of ageing? Or is the route upmarket to be found elsewhere?

As most of the world celebrates Halloween, Catalans are to be found out in the streets, roasting chestnuts and eating marzipan cakes known as panellets as part of the festival of La Castanyada. There are no gaudy masks, witches hats, gummy bears or high-camp horror here; the spirit is resolutely Iberian in its simple roots as a day to remember, and even communicate with, the deceased. Summer becomes autumn, youth turns to age, and the Catalans look the process straight in the eye.

The Castanyera herself is depicted as an elderly woman, dressed in peasant clothes with a scarf and gloves, standing over the roasting drum. There’s a fondness, a revealing romanticism at play here; the Spanish currently boast the eight-longest life expectancy in the word, with one recent study in The Lancet suggesting that it will overtake Japan in the top spot by 2040. Agedness is part of the everyday, tucked into the folds of life rather than pushed to one side.

So it used to be with Spanish wines. How many of us, during our early fumblings, remember discovering the foil-netted Gran Reservas on the supermarket shelves for a few coins more than a fruit-bomb Shiraz? The flavours were so different from everything else; dusty, spicy, earthy-sweet. There’s something autumnal - even chestnut-like - about them, with their noble agedness. The message was simple: Young = Simple, Old = Serious.

On the first day of the ‘Cava Meeting’, the Cava DO’s impressive two-day conference in Barcelona during December 2023, a tasting was organised showcasing the “most iconic” Cavas, including those that had aged for the very longest. A wine was brought out from 1975. The room was aflutter. Panellists murmured appreciatively.

I looked over at the sommelier and importer I had been sitting next to for most of the day, and it barely took a second for us both to mouth the word dead to each other.

There are tremendous old sparkling wines - and I certainly tasted some during my time in Catalonia - but this was not one of them. Why the need to wheel out such a specimen? The clue, perhaps, lay in the messaging: “Great Cavas can not be rushed”, Pedro Ballesteros MW told the crowd as the topic moved on to raising Cava’s image. “Extended ageing is very important.”

The message seemed clear as the conference went on; long-aged Cavas were the way to raise the image of the appellation as a whole, the top 10% that would “boost the whole world of Cava” according to Cava DO President Javier Pagès.

I, like many others, stopped buying those foil-netted bottles after a few months. A decade passed with barely a drop of Rioja passing my lips. Then - thanks in part to the publisher of this report - the wind carried a sense that times were changing. The truth of old wine is that 90% of it tastes just like that - old. It can lose the taste of itself, of its home, of its people. Such is the case with Cava; increasingly, as we moved onto wines of fifteen, twenty years of age, these native varieties that punch with vigour and clarity in their youth seem to congregate around a same-iness of flavour; nutty honey, funky dried citrus, earth and browned spices. There’s some impact there, often at prices far below any other sparkling wines offered for sale at such ages. But is this just another case of the wire netting at play?

Cava from 1975 in Barcelona, December 2023

Pepe Raventós of Raventós i Blanc minces no words. “We abuse long ageing on the lees and oxidative winemaking to gain power and intensity that is lacking from the grapes, in order to gain scores from the journalists”, he says as we walk through the vineyards that make his impressive - and youthful - entry level Blanc de Blancs. A few noble exceptions aside, the tastings for this report was as littered with wines over ten years old that failed to impress as with wines at five years old that excelled.

Those noble exceptions are not to be dismissed, though; Can Sala (the Familia Ferrer estate owned by the founders of Freixenet and distributed by Freixenet), together with Mestres and a few others, embody the art of ‘old-school’ Cava making, with wines that merit extended ageing and deliberately embrace a little gruff, even rustic disposition. These are wines with generational knowledge, with multiple decades of experience behind every decade in the bottle. For producers without this track record, merely pursuing ten years on lees as a route to charge higher prices does not always yield such results.

If extended longevity is more of a circus act than a genuine route to interesting Cava, then Cava has also played some cards in the arena of single terroir wines with the category of Guarda Superior de Paraje Calificado designation, essentially a system of accredited single vineyard Cavas which have to be certified by a tasting panel as to their distinct, local character. At the time of writing, though, only ten Paraje wines have been authorised, four of which belong to Cordoniu and two to Can Sala.

Beautiful - and mature - Cava from Carol Vallès

Despite the Paraje Calificado initiative being first outed in 2017, the list of producers has not grown any longer (especially since original members Recaredo, Torelló and Gramona left the appellation). One producer told me that they were not “aligned with Paraje - the restrictions are too light, with young vines and high yields allowed” (although it must be noted that Paraje’s yields are limited to 8,000 kg per hectare, 2,000 less than for Guarda Superior),

It’s fair to say that, to date, Paraje Calificado has not taken off amongst Cava’s smaller and independent producers. Cava’s annual report in 2022 listed a total of just 20,000 bottles made under the designation (out of 249,000,000), with the number one market - Belgium - buying 532 bottles. There are fine wines in the ranks of Paraje, but do they, or the ‘Elaborador Integral’ group, represent the pinnacle of terroir-focused Cava? Only in part.

What was apparent, though, is that Cava does keep within its ranks a growing band of fine, forward-looking producers who, whether they boast badges or not, are nevertheless showing wines that show the unmistakable signs of a modern, quality-orientated viticulture and a desire to fight for vivacity, energy and character in their wines.

These are the wines that would feel at home on a fine, contemporary wine list, that will be picked off the shelf in the smart wine shop, that will be picked up by the next generation of wine communicators and shown to the world. This is the 10%.

Or at least, it should be. Too many wines, across Cava, Corpinnat and Classic Penedès, still suffer from clunky branding and labelling. Sarah Jane Evans MW, speaking at the close of the Cava conference, offered up the following thoughts based on her experience talking to important UK retailer The Wine Society:

“Cava is the category with more 4 and 5 star reviews than any other. Their members’ understanding of Cava is so low that when they get a good bottle they are blown away by it!”

If terrible labels go hand-in-hand with low prices to lower expectations, then they certainly do their job. But it’s time for expectations to rise. The wines are there to do the heavy lifting, and they’re not only the gilded titans of long-ageing.

Some in Catalonia fear that the traditional Castanyada is falling out of favour, and the chestnut-roasters, with their dusty-sweet tastes of mellow maturity, might disappear from their figurative street corners to be replaced by plastic pumpkins and trick-or-treaters. Sales of panellets, though, have been steady: “Young Catalan people celebrate Halloween…but wth Panellets”, Antoni Bellart, president of the Barcelona Bakers’ Association told Catalan News, as they announced that 250 tonnes had been sold in autumn 2023.

Perhaps there’s an abandonment of heritage, a setting of the sun to worry about here.

Or perhaps people aren’t actually that keen on chestnuts.